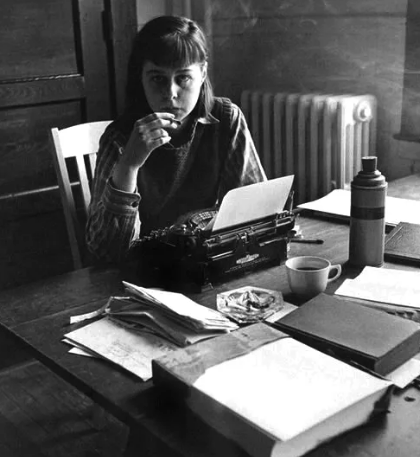

The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter was the first thing I read by McCullers, and it still holds true what May Sarton said in her early Boston Transcript review: “something has been added to our life.”

McCullers was a serious piano student in her youth, and one of the things I love most is how she describes feelings surrounding music.

How did it come? For a minute the opening balanced from one side to the other. Like a walk or march. Like God strutting in the night. The outside of her was suddenly froze and only that first part of the music was hot inside her heart. She could not even hear what sounded after, but she sat there waiting and froze, with her fists tight. After a while the music came again, harder and loud. It didn’t have anything to do with God. This was her, Mick Kelly, walking in the daytime and by herself at night. In the hot sun and in the dark with all the plans and feelings. This music was her—the real plain her.

She could not listen good enough to hear it all. The music boiled inside her. Which? To hang on to certain wonderful parts and think them over so that later she would not forget—or should she let go and listen to each part that came without thinking or trying to remember? Golly! The whole world was this music and she could not listen hard enough. Then at last the opening music came again, with all the different instruments bunched together for each note like a hard, tight fist that socked at her heart. And the first part was over.

This music did not take a long time or a short time. It did not have anything to do with time going by at all. She sat with her arms held tight around her legs, biting her salty knee very hard. It might have been five minutes she listened or half the night. The second part was black-colored—a slow march. Not sad, but like the whole world was dead and black and there was no use thinking back how it was before. One of those horn kind of instruments played a sad and silver tune. Then the music rose up angry and with excitement underneath. And finally the black march again.

But maybe the last part of the symphony was the music she loved the best—glad and like the greatest people in the world running and springing up in a hard, free way. Wonderful music like this was the worst hurt there could be. The whole world was this symphony, and there was not enough of her to listen.

It was over, and she sat very stiff with her arms around her knees. Another program came on the radio and she put her fingers in her ears. The music left only this bad hurt in her, and a blankness. She could not remember any of the symphony, not even the last few notes. She tried to remember, but no sound at all came to her. Now that it was over there was only her heart like a rabbit and this terrible hurt.

From “The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter” (101-2)

Library of America, 2001

Originally published in 1940

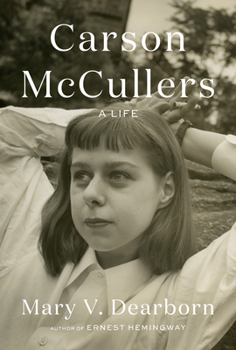

Interestingly, according to Mary V. Dearborn, the title may have been “drawn from “The Lonely Hunter,” a poem by a man who wrote as a woman. William Sharp, a Scottish editor with a mystical bent, was his “truest self” in the poems he wrote as Fiona Macleod. The poem reads, in part, “But my heart is a lonely hunter that hunts on a lonely hill.” Its title and the poet’s gender-ambivalent identity would have appealed to Carson” (75).

Dearborn’s book, Carson McCullers: A Life (Knopf, 2024), is an excellent dive into McCullers’ short yet dynamic life. While it’s long and a bit repetitive (clocking in at 420 pages and going fairly in-depth into the lives of her family and friends as well), I do appreciate the detail. And if you are looking to do further research on McCullers, extensive notes are included.

The book not only extensively covers McCullers’ life but is a who’s who of the literary and arts scene of the time period. You can really go down the rabbit hole, as Carson surrounded herself with so many talented and interesting people.

I also happened upon this deep dive: Unladylike: Political Participation and White Womanhood in Southern Gothic Literature, an honors thesis by Riley Morgan (2021). Really interesting and lots of great citations exploring work by McCullers, Flannery O’Connor, and Eudora Welty.

Read-alikes:

Flannery O’Connor, The Complete Stories

Katherine Anne Porter, The Collected Stories

Eudora Welty, The Collected Stories